Crimeware explained: What it is and how to stay safe

Cybercrime is an increasingly unavoidable part of digital life, and it’s supported by a growing ecosystem of malicious tools and services. The term “crimeware” is sometimes used to describe that ecosystem, especially when the goal is to highlight how cybercrime is enabled.

Because crimeware doesn’t have a single, universally accepted definition, different sources use the term differently. This guide uses a practical definition, explains how it overlaps with malware, and outlines ways to reduce exposure.

What is crimeware?

Crimeware is a somewhat niche term in cybersecurity circles. As such, different sources and experts may disagree on the exact meaning. In this guide, crimeware refers to a broad spectrum of programs, tools, or digital systems used to support cybercrime. This can include common forms of malware (such as ransomware, trojans, and spyware), as well as supporting infrastructure, like illicit marketplaces, credential-leak sites, or services that help operators run attacks at scale.

How crimeware differs from malware

Malware is generally defined as malicious software designed to disrupt, damage, steal data, or gain unauthorized access to systems. Crimeware is a broader term that can include malware, as well as the services and platforms that enable cybercrime.

Though there is overlap, crimeware can exist without malware. For example, sites hosting leaked data or platforms that advertise Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) may support attacks without directly infecting visitors.

The reverse can also be true: some tools used in intrusions are dual-use and appear in legitimate security testing. For example, Mimikatz is widely described as a post-exploitation tool for extracting credential material and is discussed in defensive contexts, even though attackers frequently abuse it. Whether something is treated as “malware” often depends on intent and how it’s deployed.

Should hardware and infrastructure count as crimeware?

Another key distinction is that, unlike malware, crimeware can include physical devices and network infrastructure as well as software. Such things may not directly infect devices like a traditional virus does, but they are still used to further criminal ends.

On the hardware side, card skimmers used to steal credit card info out in the real world are a type of crimeware. Malicious USB sticks and botnets used to spread threats likewise fit under the crimeware umbrella, as do hardware keyloggers.

Such devices are clearly illegal and directly cause harm to those who come into contact with them. On the other end of the spectrum, dark web marketplaces and the sites and services where cybercriminals sell their products and services do not generally cause direct harm to visitors.

Servers supporting cybercriminal sites and networks used by scam callers are all tangled up in wider criminal enterprises. As such, it would seem reasonable to consider them crimeware, even if the underlying technology is not always directly causing harm.

Who uses crimeware and why

Cybercriminals are a broad group, ranging from individual opportunists to organized groups. Some state-linked groups likewise conduct cyber operations (though whether these are considered criminal depends on attribution and the legal framework applied).

In “as-a-service” models, operators provide tools and supporting infrastructure to affiliates, which can lower the barrier to entry for less technical actors. More capable groups may use automation and dedicated platforms to scale operations, coordinate affiliates, and run key parts of an attack workflow (such as distribution, payments, and leak-site pressure).

In short, crimeware can expand participation in cybercrime and help those already involved operate at a greater scale and with greater efficiency, whether the goal is financial fraud, the theft of sensitive data, or extortion.

How does crimeware work?

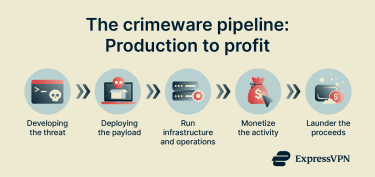

Crimeware is extremely diverse, so there is no single way that it is created or that attacks are carried out. Still, many cybercrime operations rely on a repeatable ecosystem of tools, services, and roles that can be viewed as a pipeline. These steps aren’t always linear, and the same actor may handle more than one.

Here’s a quick overview of the main moving parts:

- Threat creation: Someone develops malware, scam tooling, or supportive infrastructure. In some cases, these capabilities are kept in-house; in others, they’re sold or offered “as-a-service."

- Payload distribution/delivery: A person or group deploys the threat, either by targeting specific people or taking a broader approach. The exact method of delivering the threat can vary wildly depending on the operation and goals.

- Infrastructure management: Operators maintain the systems and platforms that support attacks, including hosting, management panels, communications channels, and other services that keep an operation running.

- Monetization: Participating in the criminal system profits in various ways. This may be achieved through fraud, extortion, or the sale of access and stolen data through illicit markets.

- Laundering: Proceeds are often moved through steps intended to obscure their origin and reduce the risk of seizure, sometimes using intermediaries or specialist services, and sometimes handled directly by the criminals themselves.

From malware to marketplace

Crimeware is sometimes used with a commercial or "productized" connotation, especially when referring to tools and services designed to enable cybercrime and offered for sale or subscription in underground communities. In other contexts, the term is used more broadly for digital instruments used in cyberattacks, whether or not they're sold.

In any case, the process begins with development. This can include creating malware, developing scamming tools, or producing hardware with criminal applications.

Once created and tested, these capabilities are put into use. They might be used directly by the original group, shared with affiliates, or sold.

Underground marketplaces can sell malware and hacking tools and may also trade in stolen data, such as credentials or payment card information. In either case, someone or a group has to be responsible for running the servers that host the marketplace and for handling payment processing.

Delivery and abuse paths

At some point, the threat needs to reach targets. As threats vary, so too do delivery methods.

Malware is commonly deployed through several well-known methods. Cybercriminals may host websites that deliver drive-by downloads to visitors, upload malicious software to file-hosting sites, or spread malware via email attachments. Others abuse software vulnerabilities to gain initial access or execute code, sometimes at scale and sometimes in targeted operations.

For crimeware that doesn’t fit neatly under the malware label, it’s often less about delivering a payload and more about operating systems that enable cybercrime. This can include running marketplaces that sell stolen passwords or credit card numbers, managing scam operations, or committing identity theft using data that has already been stolen.

The role of automation and the "as-a-service" model

Many profitable cybercrime ecosystems increasingly rely on automation and service-style monetization. This has helped some groups operate more like businesses, with specialized roles and repeatable workflows.

Automation can speed up and scale key steps, such as running high-volume campaigns, managing infrastructure, and processing stolen data. Some “crimeware” in this broader sense is less about a single malicious payload and more about tools and platforms that support operations.

One common expression of this is the “as-a-service” model. In Crimeware-as-a-Service (CaaS) and RaaS, operators provide tooling and infrastructure while affiliates carry out intrusions and share profits.

For example, many phishing operations use breached data (and other publicly available information) to identify targets and tailor messages. Automation can also support credential stuffing (testing stolen username/password pairs at scale) and, in fraud schemes, the validation of stolen payment-card details. Phishing kits and Phishing-as-a-Service (Phaas) platforms lower the barrier even further by letting less-skilled actors spin up and manage phishing sites, typically distributed via malicious links.

This model can apply to both infrastructure and software. For example, cybercriminals may rent out access to botnet resources or serve as access brokers to valuable systems that they have already compromised.

Categories of crimeware

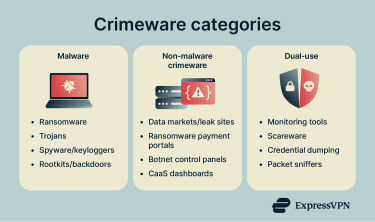

Crimeware is a broad term that covers a wide range of tools. Some are primarily designed for criminal use, while others are dual-use and become "crimeware" mainly through their deployment. The term can also be used to include software, hardware, and digital platforms that support cybercrime.

Malware used in cybercrime

A large portion of crimeware consists of malware. Common examples include:

- Ransomware: Malware that encrypts files or locks access to data and demands payment to restore access.

- Trojans: Dangerous programs that masquerade as legitimate software to trick users into installing it.

- Spyware and keyloggers: Malware that monitors activity or records keystrokes to capture sensitive information and send it to an attacker.

- Backdoors and rootkits: Tools that enable unauthorized access or maintain hidden, privileged control of a compromised system.

When used to enable cybercrime, these tools can fall under the broader “crimeware” label.

Crimeware that isn’t malware

This category includes crime-enabling services and infrastructure, not a payload on a victim device. Common examples include stolen-data markets and leak sites, ransomware payment/leak portals, botnet management panels, and CaaS dashboards used to distribute tooling to affiliates. These platforms aren’t limited to the dark web; some appear on the open web or mainstream services until they’re disrupted.

Physical devices can play a role, too, such as card skimmers and packet sniffers.

Dual-use tools and the gray area

There exist many tools that may or may not be crimeware depending on intent and how they’re used. This gray area encompasses both hardware and software.

Some products labeled “spyware” are sold as employee-monitoring or parental-control tools. Whether they’re lawful depends on the jurisdiction and factors such as notice, consent, and how collected data is handled.

Scareware is often a deceptive tactic that uses fear (e.g., fake security alerts) to prompt downloads or payments. It may be more likely illegal under fraud or consumer-protection laws, but it still depends on the specific claims made and local rules.

Tools such as Mimikatz illustrate the dual-use problem. It's widely described as a Windows credential-dumping tool that can extract plaintext passwords (and other credential material) from memory. It can clearly be used maliciously, but it’s also used in legitimate security testing; the line is usually crossed when it’s used to access credentials without authorization (and some malware incorporates similar capabilities).

AI tools can also be abused. Law enforcement has warned that criminals can use generative AI to scale social engineering and phishing-like fraud by producing more believable content with less effort.

On the hardware side, packet sniffers are not necessarily illegal. But given their ability to monitor network traffic and intercept and analyze data packets, these tools can be misused when deployed without authorization.

How to reduce the risk of crimeware

Many standard cybersecurity practices can help reduce the likelihood and impact of crimeware-driven attacks.

Protecting against malware-driven attacks

Antivirus and endpoint security tools can detect and remove many kinds of malware used in cybercrime, from keyloggers to trojans. Many robust cybersecurity tools will also scan downloaded files and active processes for threat signals.

Some security tools also block access to known malicious websites. ExpressVPN's Threat Manager is designed to prevent apps and sites from communicating with known trackers and parties associated with malicious behavior, and it can help block known malicious domains.

Caution with downloads still matters; malicious attachments, links, and file downloads remain common delivery paths for malware.

Regular backups can reduce the damage from ransomware, especially when backups are kept offline/secured, and restores are tested.

Reducing exposure to crimeware ecosystems

Credential abuse often succeeds when passwords are weak or reused. Helpful steps include:

- Use strong passwords: Makes it harder for attackers to break into accounts using common-password lists or password-guessing attacks.

- Use unique passwords: Limit fallout from breaches. If you reuse passwords across accounts, a single breach can have a widespread impact.

- Enable multi-factor authentication (MFA): Adds a second check beyond a password, which can still protect an account even if a password is stolen.

- Get a password manager: Helps generate and store strong, unique passwords securely (instead of reusing weak passwords or storing them in plaintext).

FAQ: Common questions about crimeware

What is the difference between malware and crimeware?

Malware is typically defined as malicious software designed to disrupt systems, steal data, or enable unauthorized access. Crimeware is used inconsistently, but can be seen as encompassing the broader tools and services that enable cybercrime. In practice, the difference often lies in purpose and context; malware is one common component, but criminals may also rely on legitimate services or dual-use tools within a crimeware ecosystem.

Can crimeware infect mobile devices?

Mobile devices are targeted by malware used in cybercrime, including trojans, ransomware, spyware, and adware. Using a mobile device doesn’t automatically eliminate risk; many attacks focus on credentials, fraud, and social engineering rather than a specific device type.

How do cybercriminals monetize crimeware?

Common monetization paths include financial fraud, data theft, and extortion. Stolen data may be sold on illicit markets or used for account takeover and blackmail-style schemes.

What is Crimeware-as-a-Service (CaaS)?

CaaS is a model in which criminals develop or operate tools and infrastructure, then sell or rent access to others, often lowering the barrier to entry for less technical actors. This can include “as-a-service” platforms where operators support affiliates who run campaigns and share profits.

Take the first step to protect yourself online. Try ExpressVPN risk-free.

Get ExpressVPN