What is the OSI model? Understanding its layers and functions

Modern networks underpin everything from everyday web browsing to large-scale cloud systems, and their moving parts can be hard to describe consistently. The Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model is a standardized reference model that explains network communication by dividing it into seven functional layers, each with a distinct responsibility.

This article introduces the OSI model, summarizes the purpose of each layer, and explains, at a high level, how data moves through the stack and why the model remains useful today.

Introduction to the OSI model

The OSI model is a conceptual and functional framework for describing how networking functions are organized. Each layer provides services to the layer above and relies on the layer below, which helps professionals communicate clearly about where responsibilities sit and where problems may occur.

The OSI model is not itself a protocol or an implementation specification that can be deployed within a network. It doesn’t prescribe specific technologies or protocols. Instead, it serves as a conceptual framework for understanding computer networks without requiring detailed knowledge of the underlying technologies.

Historical context and importance

Multiple groups worked together to develop the OSI model. This included the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the International Telegraph and Telephone Consultative Committee (CCITT), later renamed Telecommunication Standardization Sector (ITU-T). First published as ISO 7498 in 1984, the OSI reference model has seen widespread adoption as a conceptual framework and shared vocabulary.

Before the OSI model, many organizations were responsible for developing their own network architectures, without a common bank of ideas, principles, and terminology to rely on. This caused many issues, and there was an active debate over the best way to build networks.

On a practical level, the OSI proposals lost out in the 1990s to the Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (TCP/IP) protocol suite. This is the system on which the modern internet is based. TCP/IP predates OSI and simplifies network design by merging and adapting several OSI layers.

Unlike the OSI reference model, TCP/IP defines specificm widely deployed protocols, making it a practical guide for implementing and operating internet architectures.

That said, the OSI model persists on a conceptual level. To this day, it provides a formalized vendor-neutral framework for describing network functions and thinking about interoperability. The model has not changed much over the last few decades and is still documented as ISO / International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) 7498-1:1994 (reviewed and confirmed in 2000).

Its role has shifted from a design target to a shared vocabulary for education, troubleshooting, and documentation, but it nonetheless remains relevant.

Key benefits of adopting the OSI model

The OSI model offers several benefits to network engineers, administrators, and organizations that work with network communications:

- Facilitate knowledge sharing: With a common terminology and framework, engineers can more easily communicate, share information, transfer skills, and work on network standards. It’s also a useful tool for educating new generations of IT professionals on well-established concepts.

- Accelerate research and development: The OSI model helps modularize network function descriptions, with each layer representing categories of technologies and protocols. Separating networking into layers makes it easier to reason about changes and improvements without redesigning the entire system.

- Support standardization efforts: The OSI model remains a shared, vendor-neutral reference model for describing network functions and how different parts of a networked system relate to each other.

- Simplify troubleshooting: The 7-layer model helps teams isolate issues by mapping symptoms to likely problem areas at specific layers, which can reduce unnecessary disruption when resolving a single bug.

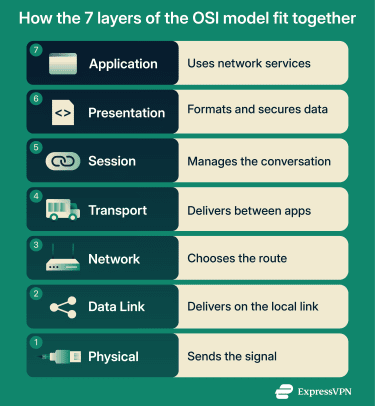

The seven layers of the OSI model

The layers are listed below, from the highest (the application) to the lowest (the physical layer). Each level of the OSI model acts as a link in the communication chain; if one is broken, a message or data may not reach its intended destination reliably.

Layer 7: Application layer

This is the highest layer in the OSI model, and the one users interact most closely with. When we communicate over a network, we usually do so through applications such as email clients, social media apps, or browsers that connect to online services.

Layer 7 protocols are implemented within applications. Their main purpose is to prepare application-generated data for downstream layers. Common protocols include:

- Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP): Facilitates the transmission of web content between web browsers and web servers (delivers HTML, images, videos, and more).

- Domain Name System (DNS): Translates human-readable domain names (hostnames) such as example.com into IP addresses.

- Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP): Transmits emails over an IP network (primarily for mail transport between servers and for email submission).

- File Transfer Protocol (FTP): Transfer files between devices or servers over networks (designed for reliable, efficient transfer).

In addition to enabling end-user applications to interface with network services, layer 7 enables remote resource sharing, file access, and network management.

Importantly, the application layer doesn’t refer to the end-user applications themselves, only to the protocols they use to communicate over a network.

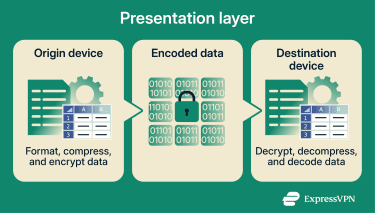

Layer 6: Presentation layer

Also known as the syntax layer, the presentation layer ensures that the received data is translated into a format the receiving layer can interpret. The presentation layer is also responsible for handling processes like encryption/decryption, encoding/decoding, serialization, and compression.

Also known as the syntax layer, the presentation layer ensures that the received data is translated into a format the receiving layer can interpret. The presentation layer is also responsible for handling processes like encryption/decryption, encoding/decoding, serialization, and compression.

Presentation-layer functions are often implemented inside individual applications or libraries. For example, an email client may use S/MIME (Secure/Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions) or Pretty Good Privacy (PGP) to encrypt message contents before transmitting them over the network. The recipient's client can then decrypt the message using the corresponding standard and keys, allowing it to be displayed in plaintext.

The presentation layer is also responsible for converting between different character encodings, such as American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) to Extended Binary Coded Decimal Interchange Code (EBCDIC) or Unicode Transformation Format (UTF)-8 to UTF-16. It can also support media encoding and compression formats, such as JPEG and MPEG.

A number of lower layers also encapsulate and package data in abstract ways to facilitate efficient network transfer. That is, they may alter the structure (headers/tailers) but will not generally change the payload content.

At its core, the presentation layer ensures that the received data is transformed into a format that applications or recipients can understand.

Layer 5: Session layer

As the name implies, the session layer establishes temporary communication sessions between two applications or processes. A session opens when two applications indicate an intent to communicate with each other and closes when one side terminates it or the connection times out.

The session layer continues to manage the lifecycle of these sessions, including initiation, data synchronization, recovery, and termination. This helps participating systems maintain a consistent, organized interaction over time.

A vital responsibility of the session layer is to define synchronization points during a session. If the session gets interrupted, these synchronization points can help systems reset to a known state and resume from an agreed point, although the meaning of these points (for example, what counts as a “checkpoint”) is defined by the session’s users, not by the session layer itself.

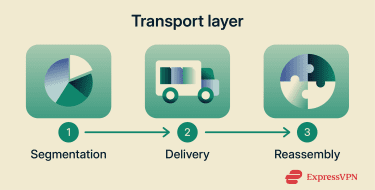

Layer 4: Transport layer

The transport layer supports a number of activities to facilitate end-to-end communication between two applications.

The transport layer supports a number of activities to facilitate end-to-end communication between two applications.

First, a segmentation process divides data into smaller units for transmission. In protocols like Transmission Control Protocol (TCP), these units are numbered so they can be reassembled in order upon arrival.

Unlike the presentation layer, however, the transport layer doesn’t alter the data's contents, format, or meaning. Rather, it segments and encapsulates the data to improve transmission efficiency.

TCP and User Datagram Protocol (UDP) are two of the most widely used layer-4 protocols. TCP provides reliable, ordered delivery with flow control and congestion control, and it can recover from losses through retransmission, which is commonly used for web browsing and email. UDP provides a lightweight datagram service with integrity checking (checksum) but no built-in reliability, ordering, or congestion control, often used for low-latency applications like real-time streaming and many online games, where some loss can be tolerated or handled by the application.

Layer 3: Network layer

The network layer is responsible for logical addressing and routing, enabling data to travel between hosts across different networks. It determines how packets are forwarded from a source to a destination, regardless of the underlying physical network structure.

In this layer, data segments from the transport layer are encapsulated into discrete units called packets. If a packet is too large for a link along the path, it may be fragmented to fit the path’s maximum transmission unit (MTU).

Network protocols then select the best available routes for these packets to reach their destinations. This process, known as routing, relies on a routing table that maps destination prefixes to next-hop addresses and includes metrics used to evaluate each possible path.

As a result, this layer is also responsible for IP addressing and packet forwarding. Typical network layer protocols include the Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP), the Internet Group Management Protocol (IGMP), and the Routing Information Protocol (RIP).

Layer 2: Data link layer

The data link layer handles communication between devices on the same network or network segment, such as a local area network (LAN) or wireless LAN (WLAN).

In Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) 802 networks, it is commonly described as two sublayers: the Logical Link Control (LLC) and the Media Access Control (MAC). Each network interface uses a MAC address (typically unique on the local link), and the LLC sublayer acts as an intermediary between the MAC and network layers.

Like the transport layer, the data link layer may provide functions such as error detection (for example, by verifying frame checksums) and, in some technologies, flow control or link-layer retransmission. It also encapsulates network-layer packets into frames, which include addressing and error-checking information.

When connecting to an internet-based server, the data link layer handles transferring frames across the local link to the next hop (for example, between a PC and a home Wi-Fi router). From there, the network layer takes over, routing packets onward toward the destination.

Common data link layer protocols include Ethernet (wired LANs), IEEE 802.11 (Wi-Fi) for WLANs, and the Point-to-Point Protocol (PPP) for point-to-point links.

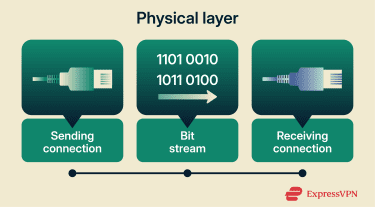

Layer 1: Physical layer

This layer encompasses the hardware and signalling conventions that physically connect devices in a network. Its primary purpose is to transmit raw bits over a physical medium. This involves media such as copper cabling, fiber-optic links, and radio links, as well as physical-layer equipment, including connectors, transceivers, and repeaters.

This layer encompasses the hardware and signalling conventions that physically connect devices in a network. Its primary purpose is to transmit raw bits over a physical medium. This involves media such as copper cabling, fiber-optic links, and radio links, as well as physical-layer equipment, including connectors, transceivers, and repeaters.

One of the key functions of these devices is to convert the bits that make up data into signals that the transmission medium can carry. This usually means translating a stream of 1s and 0s into electrical, optical, or radio signals.

The physical layer on both ends must agree on a signal convention for representing the bit stream. It’s also responsible for controlling the transmission rate (typically measured in bits per second) and defining characteristics of the physical link, such as timing, connectors, and the physical medium in use.

Once data exits the physical layer, it goes to the data link layer, which begins framing the bit stream for local delivery (including link-layer addressing and error detection).

How does data flow through the OSI model?

Applications and humans consume data in many different shapes, sizes, encodings, and file types. At the lowest level, network hardware transmits data as bits.

Each layer plays a different role in preparing application-generated data into a uniform stream for efficient network transport and interpretation at the destination. The data is progressively encoded, structured, and packaged as it moves through the stack.

Real-world example of how to apply the OSI model

As an example, consider an email exchange between two individuals. The sender writes an email using an email client (or a webmail interface). When they send it, the application layer uses a specific protocol, such as SMTP, to standardize the data format. It’s then sent to the presentation layer, which may compress, format, and/or encrypt the data.

The data then moves through the stack: transport, network, and data link layers prepare it for delivery by segmenting, packaging, and framing it. The network and data link layers use IP addressing and link-layer (MAC) addressing to determine where the data should go and how it should get there.

Finally, the physical layer represents the bit stream as signals that can traverse physical media, such as Wi-Fi radio waves or fiber-optic cables, to reach its destination.

Once the data reaches the recipient's device, it reverses its path back up through the model layers. The lower layers reconstruct the data before passing it upward. The presentation layer may decode or decrypt the data as required before passing it back to the recipient’s application layer in the email client. Finally, the application layer delivers the message so it can be displayed to the recipient in human-readable form.

FAQ: Common questions about the OSI model

What does the OSI model explain?

The Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model explains the different components of a network, how they interact, and how data flows across a network. It serves as a reference model for essential networking concepts. The seven layers of the OSI model show how data moves from the sender through the network to the recipient in a useful form.

Why is the OSI model still relevant today?

The Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model remains a useful and widely accepted model for understanding network architectures. While the modern internet isn’t explicitly based on the OSI model, it’s underpinned by a similar design and principles. The OSI model is also very popular as an educational tool to learn the fundamentals of how networks operate.

What are the 7 layers of the Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model in order?

Application, presentation, session, transport, network, data link, and physical. Communications start from the application layer on the sender’s device and move down through the layers until they reach the physical layer (then move back up the stack on the recipient’s side).

What is the purpose of the Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) physical layer?

The physical layer refers to the physical media and signaling used to transmit raw bits over a network link. This includes items such as copper cabling, fiber-optics, wireless radios, connectors, and transceivers. It also covers how devices represent a bit stream (1s and 0s) as electrical, optical, or radio signals for transmission, and convert received signals back into bits.

How can the Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model help troubleshoot network issues?

By helping investigators pinpoint the network layer where the error occurs and providing a common language for interpreting causes and identifying fixes. For example, if there’s an error such as “the device is not connected to any network,” the problem likely lies at the physical or data link layer. One might check whether all cables are connected, Wi-Fi connectivity is disabled, or there’s physical damage.

What are common misconceptions about the OSI model?

One common misconception is that the Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model underpins all networks, even the internet. The modern internet is based on the Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (TCP/IP) suite, which shares similarities with the OSI but differs in key ways. Another is that the OSI model describes how to actually configure and deploy a network. However, it primarily serves as a conceptual framework for understanding network communication.

Take the first step to protect yourself online. Try ExpressVPN risk-free.

Get ExpressVPN